Finally! Humira’s biosimilars also hit the us market!

Humira was first marketed in 2002 and was protected in the US market until 2023, thanks to AbbVie’s use of two strategies :

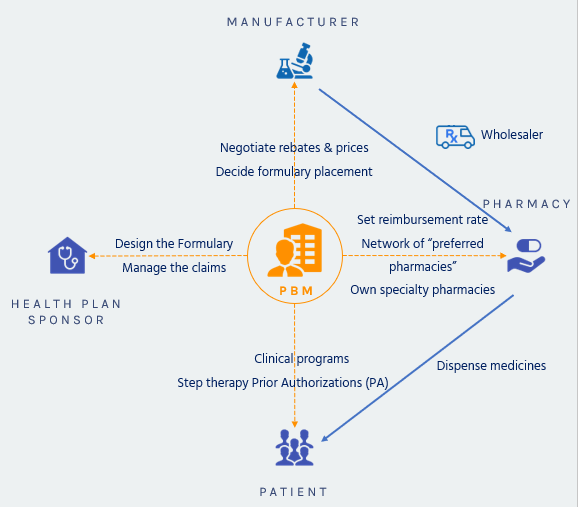

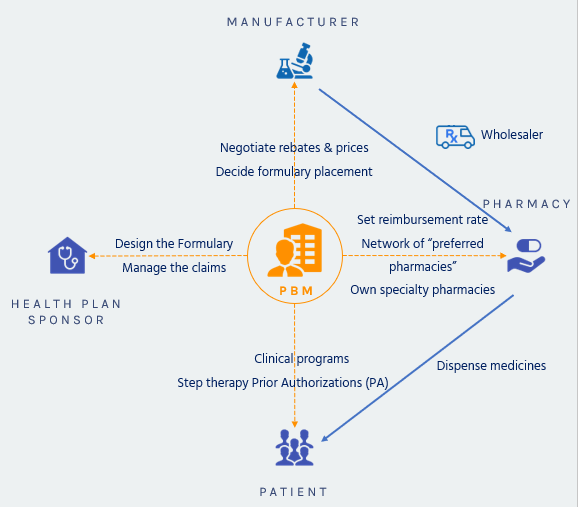

When insurance companies began offering prescription drugs as a health plan benefit in the 1960s, PBMs were created to help insurers contain drug spending. Originally, PBMs decided which drugs were offered in formularies and administered prescription claims.

In the 1970s, PBMs began to adjudicate prescription drug claims. In the 1990s, drug manufacturers began acquiring PBMs. Concerns about conflicts of interest caused the Federal Trade Commission to issue orders for divestment, sparking a series of mergers and acquisitions within the industry.

Because health care costs were increasing dramatically by the end of the 1980s, the PBM role also expanded vertically. The PBM became a big player in the dispensing of prescription drugs. One of the first players born from a national health maintenance organization, United HealthCare at that time, was Diversified Pharmaceutical Services (DPS). The company was the first to introduce cost strategies that have become core services for PBMs today. After SmithKline Beecham acquired Diversified in 1994, it played a critical role in the health care services division and became a leader in pioneering clinical programs. In April 1999, the company was acquired by Express Scripts, which strengthened it to become a leader in the health care industry as a strong PBM.

The acquisition of Caremark by CVS in 2007 marked the point where a PBM started negotiating discounts for drugs from manufacturers. They also started to provide clinical drug reviews and disease management services, which was beneficial to plan sponsors and patients.

Concerns with PBM business practices focus on transparency to consumers regarding rebates and reimbursements, particularly ‘Gag clauses’, provisions in contracts between PBMs and pharmacies that prevent pharmacists from telling patients when the cash price of a drug is less than the insurance copay price. These clauses were banned in 2018 by the Patient Right to Know Drug Prices Act, S.2554 and the Know the Lowest Price Act, S.2553 to promote transparency toward patients.

Except for these 2 laws, PBMs remained largely unregulated. Yet many states had tried to pass laws attempting to impose reasonable regulation and oversight over these corporations. Far too often, however, the PBMs gained legislative ground up in the courts. They often relied on the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to argue the states are powerless to act.

This changed in 2020, when the Supreme Court of the United States issued a unanimous decision in Rutledge v. PCMA, on Dec. 10, 2020, holding that a federal law (3), does not prevent states from enacting laws regulating the abusive payment practices of pharmacy benefit managers.

• The World Health Organization estimates that over two billion people lack regular access to essential medical products (i.e. medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics), which is exacerbated by a lack of affordability and local availability.

• The Internet has served as a disruptive force to traditional industry in the practice of pharmacy and trade in pharmaceutical products, allowing for the international sale of medical products to patients with a prescription.

• Failure to regulate the sale of medical products over the internet, including failure to differentiate between legitimate online pharmacies and rogue websites, poses a major public health risk.

• Governments are neglecting their human rights obligations when their populations do not have adequate access to affordable healthcare, including access to medical products.

They do this using 6 different tools/strategies

Negotiating Rebates from Drug Manufacturers

Manufacturers are supposed to provide a rebate if their product is preferred and put on the plan formulary, rather than a competitor’s product.

Negotiating Discounts from Pharmacies

Negotiating Discounts from Pharmacies

The same market competition mechanism is used with retail pharmacies: they will provide discounts to be included in a plan’s pharmacy network.

Offering More Affordable Pharmacy Channels

Offering More Affordable Pharmacy Channels

The PBM will promote mail-order services which generate savings on the dispensing costs, and build preferred pharmacy networks

Encouraging the Use of Generics and Affordable Brands

Encouraging the Use of Generics and Affordable Brands

Once a medication has lost its patent protection, competitors will launch “me-too” products or generics which are much cheaper than patent protected drugs.

PBMs design tiered formularies dividing drugs into groups based mostly on cost. A plan’s formulary might have three, four or even five tiers. Each plan decides which drugs on its formulary go into which tiers. In general, the lowest-tier drugs include the lowest cost generic drugs, and the highest the most expensive non-preferred brand specialty drugs. The lower the tier the lower the member’s copay.

Reducing Waste and Improving Adherence

Reducing Waste and Improving Adherence

Using formularies and tiered cost sharing, prior authorization and step-therapy protocols, consumer education, and physician outreach, PBMs try to lower plan costs.

Managing High-Cost Specialty Medications

Managing High-Cost Specialty Medications

Specialty pharmacies are another crucial tool to provide effective patient education, monitoring, and support for patients with complex conditions, such as hepatitis C, multiple sclerosis, or cancer.

Money from drug manufacturers

Money from pharmacies

Money from plan sponsors

A plan sponsor listed 9 different types of administrative fees they had been charged by their former PBM!

Money from patients

“Claw back”: non disclosed to patient or plan sponsor, this type of revenue happens when a patient’s copay exceeds the prescription cost. A 2018 USC Schaeffer study revealed that this happens in 23% of the cases! And that the mean overpayment averaged $8.

PBMs used Gag Clauses forbidding pharmacists to tell patients in case they would be better off paying cash or using copay cards rather than through their health plan. As said above, Gag clauses are now forbidden but no one can guarantee that they disappeared totally …

Humira was first marketed in 2002 and was protected in the US market until 2023, thanks to AbbVie’s use of two strategies :

After wrapping up the 2023 enrollment, employers are now planning their next moves to mitigate the continuously growing healthcare costs impacting their plans. This is particularly true for pharmacy costs.

PhRMA, a Big Pharma lobbying group, released an advertising touting that drug prices were not fueling inflation. To prove it, they produce the graphic below.

Care2Care secured a strategic partnership with an innovative, transparent, 100% pass-through PBM.

Adding to our expertise in international drug sourcing, we expand our offer to the full pharmacy benefit management.